Overview: The earliest Menorahs in the archaeological record, Josephus on the Menorah’s shape, the rabbinic and Maimonidean view, and the Chabad movement.

“And six branches coming out of its sides: three menorah branches from its one side and three menorah branches from its second side.” (Ex. 25:32)

The ambiguous verse describing the Menorah branches left a major controversy on the shape of the Menorah. Currently displayed in the Israeli emblem and Israeli coins, the iconic Menorah image has long been a symbol for Judaism in temples throughout Jewish history. In 1982, the Lubavitcher Rebbe spoke to his followers about changing the famous round-shaped Menorah with a straight-branched Menorah. He based it primarily on a Maimonidean drawing of the Temple Menorah that was publicized not too long before.[1] This stirred a Menorah controversy that continues to this day, with the Chabad movement displaying straight-sticked Menorahs worldwide, while most others continue to display a round-shaped Menorah. We will examine the available evidence after a brief, yet fascinating, history of the Menorah.

A brief history of the Menorah

The Menorah is first described in Exodus as being a part of the gold vessels in the portable temple, the tabernacle. It’s assumed to have made its way to Solomon’s temple, although the lengthy Temple description (I Kings 6-7) excludes mention of a grand Menorah. Only ten minor candelabras (Menorahs) are described as being upon the entrance of the holy Shrine (I Kings 7:49, I Chronicles 28:15, II Chronicles 4:7).[2] Be as it may, all the golden temple vessels were deported to Babylon at the destruction of the Temple (II Kings 24:13), perhaps never to be seen again in recorded history. Ezra (1:9-10) describes “many golden vessels” being returned to the Temple upon the return from Babylon, and it’s unknown if the Menorah was included. According to some Jewish folklore, the Menorah was hidden away by the Jews during the destruction of the Temple (Bamidbar Rabbah, 15:10).

The Second Temple certainly displayed a large daily-lit Menorah (Ben Sira 26:17, and perhaps as early as II Chronicles 13:11). The Menorah was eventually taken by Antiochus IV Epiphanes during his Temple raid in 169 BCE, only to be rebuilt by the Maccabees several years later (I Maccabees Ch. 1 and 4 and Menachot 28b). According to Josephus (War of the Jews, Ch. 7) as well as the Arch of Titus, the Menorah was taken to Rome, to the newly built Temple of Peace, where the Menorah likely remained until the sacking of Rome by the Visigoths or Vandals in the fifth-century. According to a questionable Jewish legend, Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, of the 2nd-century CE, saw the Menorah, alongside other Temple vessels in Rome (Sifri Zuta, Behaalotecha 8:2).[3]

The case for a straight Menorah

The Lubavitcher Rebbe made the case for a straight-branched Menorah and the worldwide Chabad movement popularized this Menorah. It was mainly due to a newly published original manuscript of Maimonides that has been in the library of Oxford University since the 17th-century.

The purpose of the drawing is to show the positioning of the decorative “cups” and “flowers,” causing some to speculate that the straight lines were merely for practical drawing purposes and not that Maimonides actually believed in a straight-lined Menorah. However, his son writes that his father believed in a straight-lined Menorah, as evident from the drawing (Avraham ben HaRambam in his commentary to Ex. 25:32).

Some argue that Rashi as well believed in a straight-lined Menorah. He comments on the words “coming out of its sides” (Ex. 25:32): “From here and there in each direction diagonally (b’alachson), drawn upwards until they reached the height of the menorah, which is the middle stem. They came out of the middle stem, one higher than the others: the bottom one was longest, the one above it was shorter than it, and the highest one shorter than that, because the height of their ends at their tops was equal to the height of the seventh, middle stem, out of which the six branches extended.”

However, it may merely be referring to a curved diagonal branch, rather than a perfectly-straight branch. The ambiguous statement is thus up for debate. In fact, early manuscripts of Rashi’s commentary often portray a rounded Menorah alongside this particular comment of Rashi.[4]

Another minor argument in favor of straight-lined branches is the word “koneh” used in the biblical Hebrew to describe the branches stemming out. The word can roughly be translated as branch, stem, or stick. In Ez. Ch. 42 it is used as a measuring rod, suggesting that the word generally refers to a straight line.[5] However, this is not necessarily the case, as it may also refer to any shaped stick, branch, or stem.

Be as it may, Maimonides as well as Rashi come more than a thousand years after the destruction of the Temple, and have not seen the Menorah – making them hardly reliable sources for its shape.[6]

The case for a round Menorah

While the earliest straight Menorahs are from the times of Maimonides and arguably Rashi, the oldest of Menorahs are all depicted as half circled branches. Some even date to the Temple Era, when people would have known the look of it from firsthand sight in Jerusalem. Even after Rashi and Rambam, Jews continued to depict mostly rounded Menorahs.[7]

Ibn Ezra on Ex. 27:21 (and Pirush Hakatzer Ex. 25:37) says that the Menorah is half-rounded “k’chetzi igul.” The natural understanding of this is that it had rounded sticks (and Menachot 28b negates other interpretations of the Ibn Ezra).

Josephus, who was an influential priest and saw the Temple firsthand, describes the Menorah branches as being trident-fashion (War of the Jews, 7).[8] Tridents are almost always circled.

The earliest Menorah paintings and carvings are all rounded. Many of them are listed here with images. We will bring a few examples:

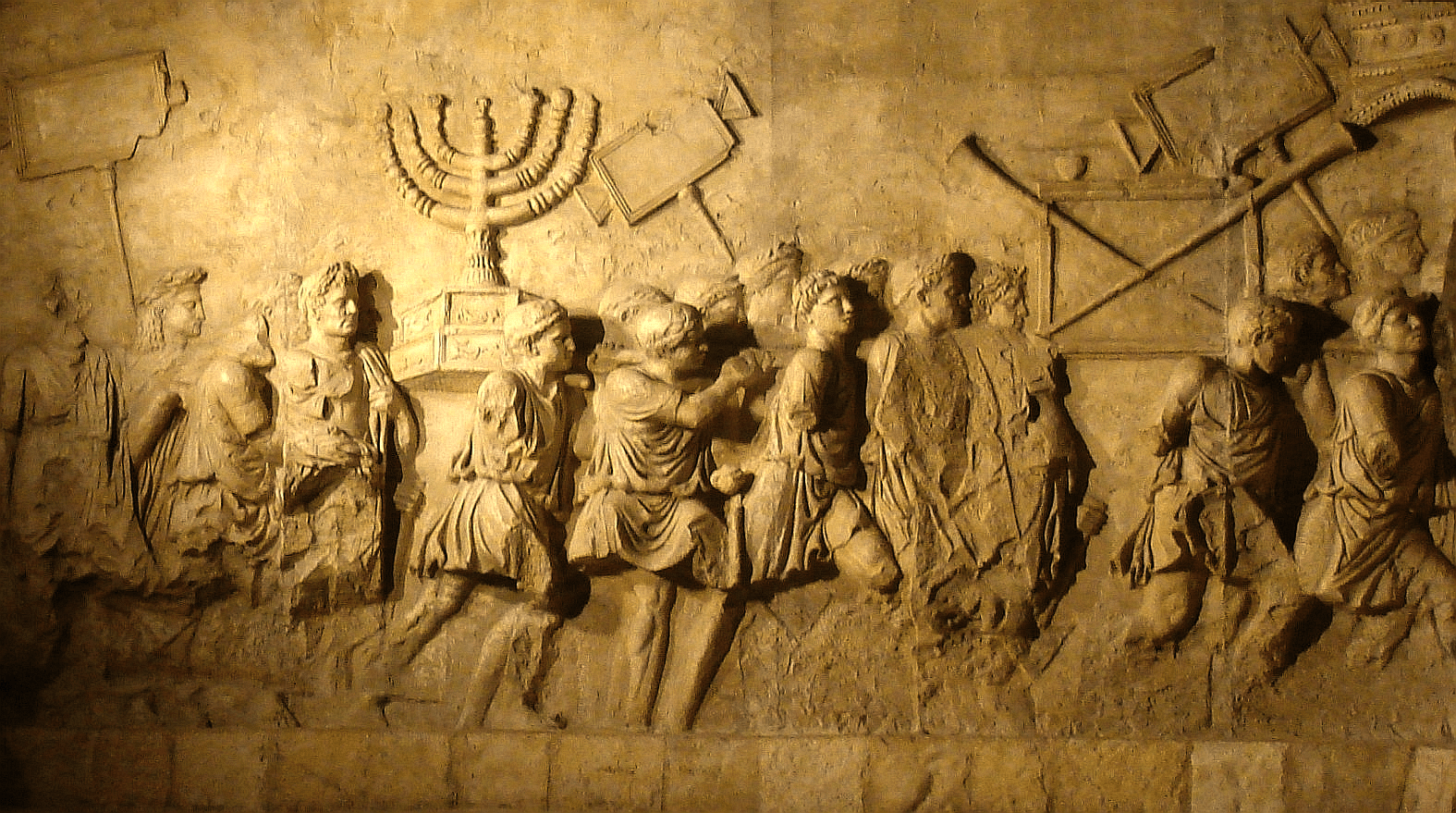

Arch of Titus built in 82 CE in Rome, depicting alongside other Temple artifacts being marched into Rome. Josephus describes the Temple utensils and Menorah being marched into Rome (War of the Jews, 7).

Some argue against this being the Menorah (suggesting instead that it was one of the minor candelabras throughout the Temple). A key argument in favor of this is the Romanized base with mythological creatures (a dragon, griffins, lions, eagles, and sea creatures) that were almost certainly absent from the Second Temple Menorah (as per the prohibition to carve animal images – Ex. 20:4, as well as the absence of these creatures in other Judaic art of the time). The base is also different from all the earlier Menorah bases that depict a three-legged base (also described as such in Menachot 28b), rather than a tri-layered base as it is in this carving.

Others theorize that the base of the Menorah went missing in transit or during the actual Temple invasion, and so it was replaced with a Romanized base. This may have some merit since the Menorah is at the center of this arch, alongside the other key temple artifacts. This would make more sense if this were the Menorah, rather than just a decoration or accessory to the Temple.

Another possibility is that this is merely an artistic twist to the real Menorah image. And one more real possibility is that the Menorah was indeed Romanized during the Roman occupation of Judea and during the time of Hellenist dominance over temple affairs.

Menorah inscription from Herodian-era mansion, Jerusalem, 1st century CE.[9]

Magdala Stone, used for Torah readings in a synagogue destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE. The base of the Menorah differs from other Menorah carvings (where there are usually a three-legged base), and according to some, is a picture of the Golden Altar that stood in front of the Menorah rather than the Menorah’s base. Yet another possibility is that the Menorah stood, with its three-legged base, atop a golden decorated base.

100 BCE – 100 CE, used with a string to seal a letter to ensure the letter’s integrity.[10]

From a synagogue at Sepphoris, in Northern Israel, of the 5th century CE. Clearly depicting the biblical Menorah with rounded branches. Many similar depictions were found in synagogues from this era.[11]

___________________

[1] Likutei Sichos, Vol. 21, p. 168-171.

[2] Menachot 98b assumes that the main Menorah was centered between the 10 additional Menorahs. Many critical scholars will suggest that the Exodus’ concept of one Menorah was invented after the First Temple era (along with the “Priestly” code) and was therefore absent from the Solomon Temple.

[3] This legend is questionable for two reasons. Firsty, it was only recorded some several hundred years after Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai. Secondly, the sages disagreed with Reb Yosei, despite him claiming to have seen the golden Tzitz in Rome, apparently not relying on his testimony (Shabbos, 63b).

[4] https://www.oxfordchabad.org/templates/blog/post_cdo/AID/708481/PostID/42051

[5] Likutei Sichos, Vol. 21 p. 169, footnote 41.

[6] As for the popular claim of them having “authority in Torah matters,” see here, here, and here.

[8] “But those that were captured in the Temple of Jerusalem made the greatest figure of them all. These were the golden table, of the weight of many talents, and a lampstand also, that was made of gold, but constructed on a different pattern from those we use in daily life; for fixed upon a pedestal was a central shaft, from which there extended slender branches arranged trident-fashion, a wrought lamp being attached to the extremity of each branch. These lamps were in number seven, and represented the dignity of the number seven among the Jews. And the last of all the spoils was carried the Law of the Jews.” (War of the Jews, 7)

[9] https://www.haaretz.com/archaeology/.premium-oldest-known-images-of-menorahs-not-what-we-know-today-1.5476274

http://seeisraelyourway.com/story-behind-menorah

[11] http://holylandphotos.org/browse.asp?s=1,2,5,36,340,468&img=INLGSPSY08