Overview: When he wrote, what he wrote, on what he wrote, what script he used, were there in-between word spaces, and more.

This discussion comes with the premise that Moses was a historical figure and wrote a Torah. How would that Torah look and how different would it have been from the Torah scrolls found in synagogue’s today. Of course, the question of Moses’ historicity and authorship of the Torah is debated extensively, but here we will avoid that discussion altogether. Instead, we will go through the various differences between Moses’ Torah and ours, as well addressing several misconceptions about Moses’ Torah.

40 years of writing

One common misconception is that Moses would have written the entire Torah, from beginning to end at the end of his lifetime. This is incorrect according to one Talmudic sage and according to the available textual evidence. According to an opinion in the Talmud (Gittin 60a), Torah was written on separate scrolls throughout the 40 years in the Wilderness and was then stitched together to make the massive Torah scroll we have today. This opinion fits well with the various sections of Torah. The many duplicate laws, abruptions in the storyline, and prefixes “and God spoke to Moses the following” separating law sections, all suggest various scrolls being written at different times only to later be stitched together.

What was written in it

The Torah text was definitely different than the one we have today. How different is up for debate but there are clearly many parts of Torah that were written after Moses’ times (see here for examples). Incidentally, Moses never claims to write the whole Torah; he is merely said to have written small parts of the text, according to the Torah itself (see here for more). Indeed, several rabbis in their Torah commentaries have come to recognize the post-Mosaic verses.

In Fact, different Torah text versions exist today, making it difficult to know which version Moses’ Torah would have had. There are also clear spelling mistakes and even parts missing from Torah, that were likely different in Moses’ Torah scroll. For example, Gen. 4:8 states “Cain told his brother Abel [missing the end of this sentence], and when they were in the field Cain set upon Abel his brother and killed him.” Surely, Moses’ version would have not been incomplete as our Torah scrolls are.

What was it written on

There’s no clear way to know what the first Torah would have been written on. It is commonly said that parchment was only invented in the 2nd-century BCE in Pergamon, Anatolia (from which the name “parchment” derived).[1] Before then, papyrus, stone, and clay tablets were the common writing materials. But this is not entirely true. There are early texts referring to people writing on animal skin (e.g. Herodotus, Histories, v. 58), as well as proto-parchments found in ancient Egypt. However, early parchment writings were extremely rare compared to papyrus writings and stone inscriptions as well as clay tablets.

Many papyri were sewn together to make a scroll if the book was very large. It is unlikely that Moses’ Torah was on stone since it is called a “book” (sefer) in the Torah (Deut. 31:24). When texts were written on stone, it was described as being written on stone (e.g. the Stone Tablets of Sinai (Ex. 34:8) and the Torah to be written on stone on the other side of the Jordan river – Deut. 27:2-3). Therefore, it remains entirely unclear on which material Moses would have written his Torah scroll, although papyrus was used much more than parchment [2] and thus a good candidate.

Scriptural amendments

The text of Torah has been edited in many different ways. Besides for the additional verses added by later scribes (see here), there was also amendments done to the entire Torah, specifically in its spelling. The rabbinic sages speak of a tikunei sofrim¸ or “corrections of the scribes,” in various different places.[i] According to many, there are 18 instances in which this “scribal correction” is applied to.[3] For various reasons, the early sages (probably the anshei kneses hagedolah[ii]) have edited the text, being that the text wasn’t standardized as it is today. For a more in-depth discussion of this topic, see here.

Besides for these “scribal corrections” mentioned sporadically in rabbinic literature, there are also the spelling amendments. In modern Hebrew, the letters vov and yud often serve as vowels. The Hebrew script lacks vowels, and the only exception is the vov and yud. But these two letters haven’t always existed as vowels. Archaeology has shown that the before the 8th century BCE, the letters vov and yud have not been used as vowels.[iii] But our Torah scroll today does have those letters as vowels many times. This is because the sages and scribes have made changes to the Torah as the Hebrew script and spelling have changed. (This concept is called malei and chaser in Talmudic terminology.)[iv]

Script of Torah

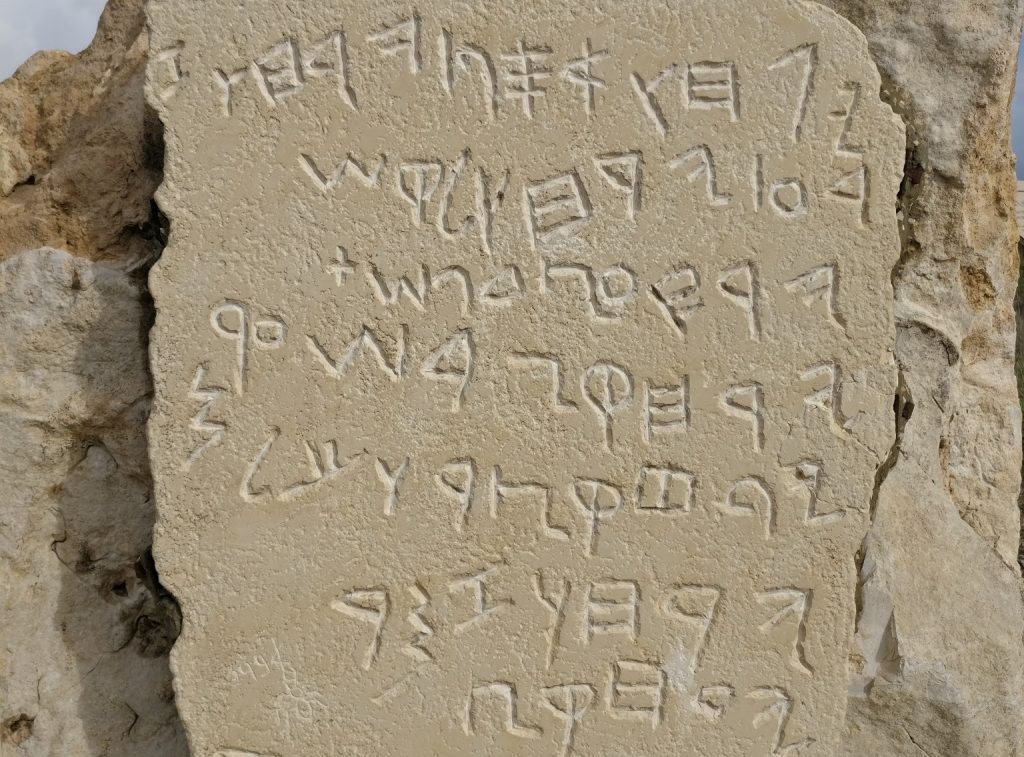

The Hebrew letters as we have them today in the scroll, were not invented until several hundred years after Moses’ death. This is affirmed by the hundreds of archeological inscriptions found of that era. This is recognized by at least one Talmudic opinion (in Megillah 2b and Sanhedrin 21b-22a). The modern Hebrew letters are Aramaic in origin (called ksav ashuris in Hebrew and the Talmud), while the older alphabet script is known as paleo-Hebrew or Phoenician script.[4]

Some suggest that the ancient Hebrew script was used for mundane documents and the Hebrew script as we have it now was used for holy documents as the Torah.[5] But this theory is very unlikely for several reasons. First off, there’s no reason to say this novel idea that isn’t attested to anywhere in the Talmud or early rabbinic writings. Secondly, as far as archaeology is concerned, the modern Hebrew script wasn’t invented until several centuries after the giving of the Torah at Sinai and was adopted from the Aramaic script. Third of all, many scrolls were found that imply otherwise. These Second Temple era scrolls are written in modern Hebrew alphabet or in Greek but when they come to writing the Name of God, they replace it with the ancient Hebrew script. This is the very opposite of what this theory is suggesting. Similarly, while the general masses turned to the modern Hebrew script, the royal writings remained in the native-born ancient Hebrew script (as can be seen on the coins of the Maccabean era and of Bar Kochba). Obviously, then, the ancient script was the more revered one, and not the Ashurit script now used.

For a chart of the evolution of the Hebrew alphabet script, see here. This earlier script had no final forms (sofit-letters) like the long mem, nun, peh, tsade, and kaph. The Talmud (Megillah 2b-3a) cites a tradition that these sofit-letters were invented by the Prophets of Israel. This statement is later reinterpreted by Talmudists to mean that they reminded the people how to use them. The early Hebrew alphabet script had no sofit-letters.

Spaces between the words

Modern writing, including Torah scrolls, have spaces separating the words. The earliest writings in Israel, including in Moses’ times, have no spaces between the words, since that way of writing was not yet invented. For examples of ancient Hebrew inscriptions, see here, here, here, and here. Until about the 7th-century BCE when spaces began to be used, lines and dots were often used to separate words.

Earliest document with actual spaces between the words is at least 500 years after Sinai. Lines and dots were sometimes used before that.[6] (See here and here respectively.) Spaces first appeared in Aramaic texts and scarcely in late Phoenician texts. We can thus assume that Moses’ Torah lacked spaces between the words, and instead was written in scriptio continua or with dots or lines.

Since there were no spaces between the words, the texts had no issue starting on one line and continuing the word into the other (as seen in the Gezer Calendar), although usually not preferred in ancient writings.

Next time I hear the Torah reading, I will pause before citing:

וזאת התורה אשר שם משה לפני בני ישראל

“This is the Torah that Moses gave to the Jewish nation” – but with their additions, enhancements, and adopting from other cultures.

___________________

[1] https://www.papersizes.org/paper-history-overview.htm

http://www.historyofpaper.net/paper-history/history-of-parchment/

[2] Besides for mundane writings which were usually engraved into broken pottery shards.

[3] According to some counts the following are the eighteen instances of Tikunei Sofrim: Genesis 18:22, Numbers 11:15, 12:12 (2X), Samuel 3:13, 16:12, 1 Kings 12:16, Chronicles 10:16, Jeremiah 2:11, Ezekiel 8:17, Hosea 4:7, Habakkuk 1:11, Zechariah 2:12, Malachi 1:13, Psalms 106:20, Job 7:20, 32:3, Lamentations 3:19.

[4] And going even farther back (ca. 1500 BCE), we have the semi-hieroglyphic Proto-Sinaic script.

[5] Ritva (on Megillah 2b) and Maharal in tiferes Yisroel 64.

[6] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/249242783_Scriptio_continua_in_early_hebrew_Ancient_practice_or_modern_surmise

[i] See Rashi on Genesis 18:22 taken from Bereshit Rabbah 49:7. See also Midrash Tanchumah on Beshalach 16. Shemot Rabbah 13:1

[ii] Midrash Tanchumah on Beshalach 16.

[iii] Dating the Old Testament by Craig Davis p. 504.

[iv] See Kiddushin 30a that says that we are not proficient in defective and plene spelling.